What Role Should Cash Play in Your Portfolio?

There are good reasons to hold cash, but also some not-so-good ones.

Cash has gone from the asset class that everyone loves to hate to a newly beloved member of the investment world. As the Federal Reserve has repeatedly hiked interest rates in an effort to tamp down inflation, yields on the three-month Treasury bill climbed to 5.11% as of June 9, 2023—the highest level in nearly 20 years. Assets in money market funds have surged, accumulating about $770 billion in net inflows for the trailing 12-month period through May 31, 2023.

Money has also flooded into high-yield savings accounts, such as Apple Savings. Savers don’t even have to be constrained by the $250,000 limit (per depositor, per bank) on FDIC insurance. Companies such as Betterment and Wealthfront now offer more generous FDIC insurance limits ($2 million and $5 million, respectively) by working with a network of partner banks.

While the growth in yield has undoubtedly made cash look more appealing, are investors overdoing it with too much of a good thing? In this article, I’ll delve into when cash does—and doesn’t—make sense as a portfolio addition.

When Does It Make Sense to Hold Cash?

Emergency fund: The best reason to hold cash is to cover unexpected spending emergencies, such as fixing a car, paying for a medical bill, replacing a home appliance, or covering basic living expenses if you lose your job. Sure, you could probably pay for most of these things using a credit card, but that convenience comes at a steep cost: Credit card rates currently average about 21%, according to Federal Reserve Economic Data. Once you borrow more than you can afford to pay off by the end of the monthly billing cycle, you might find yourself deeper and deeper in debt as interest charges start piling up.

Most financial advisors recommend keeping at least three to six months’ worth of monthly living expenses in safe, highly liquid assets such as an FDIC-insured bank savings account, money market fund, or cash management account. If you’re the sole breadwinner for the family, rely heavily on sales commissions as a major part of your total compensation, or if you’re a freelance worker with unpredictable income, you might want to keep as much as 12 months’ worth of monthly expenses in highly liquid assets.

Short-term bucket for retirement spending: The concept of retirement bucketing, originally developed by Harold Evensky, involves dividing a portfolio into separate groupings, or buckets, based on when spending will need to happen. Evensky and other financial advisors often recommend that retirees keep at least one or two years’ worth of spending in cash or other short-term securities. This strategy can facilitate retirement spending from an administrative standpoint because withdrawals are more easily made from cash instead of selling off assets within the portfolio. It also helps mitigate sequence-of-returns risk, a problem that can arise when a period of poor market performance early in retirement results in larger-than-average portfolio losses, making future portfolio withdrawals more difficult to sustain.

Other short-term spending needs: Earlier this year, Morningstar published a new Role in Portfolio Framework that articulates best practices for matching up different types of funds with an investor’s time horizon. If you’re saving up for an anticipated spending need in the next one or two years—a wedding, a new car, a major vacation, a down payment on a house—cash is probably the best parking spot. That’s because it doesn’t run the risk of suffering in a market downturn, which could force you to sell at a loss or run the risk of not having enough assets available to pay for the anticipated expense.

After receiving assets from an inheritance or other sudden financial windfall: If you receive a sudden influx of assets, you might feel pressure to do something with the money right away, and making a rash decision such as buying a boat, vacation home, or high-cost whole life insurance product might lead to later regret. Financial advisors often counsel against making sudden moves after a windfall, especially when it’s related to the death of a spouse or close family member. Grief can be overwhelming, and it’s easier to make sound financial decisions once some of the initial emotional trauma has settled a bit. Instead, it’s helpful to take more time to carefully consider your financial objectives and how the new assets might best fit into a well-diversified portfolio.

When Doesn’t It Make Sense to Hold Cash?

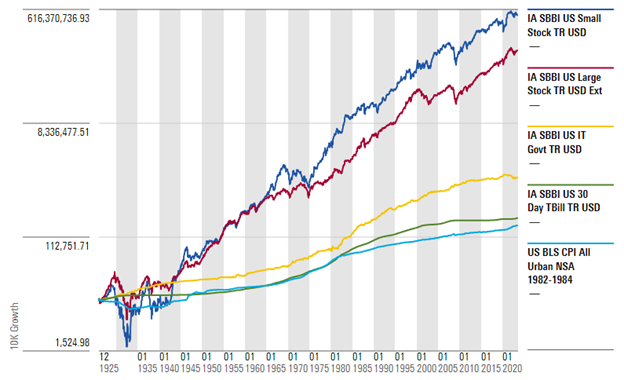

Long-term spending and investment needs: Morningstar’s Role in Portfolio framework (mentioned above) includes four different time-horizon groupings: 1-2 years, 2-6 years, 6-10 years, and greater than 10 years. In most cases, significant cash allocations only make sense for goals with the shortest time horizons (1-2 years or less). For time periods longer than that, other asset classes typically offer better growth potential, as shown in the graph below.

Long-Term Asset-Class Returns

Cash can be particularly detrimental to long-term investment goals such as retirement. A retiree who started saving $10,000 per year in 1993 and stashed everything in cash would have ended up with about $380,000 by the end of 2022, compared with about $1.5 million if the savings were invested in an all-equity portfolio or $1.0 million if invested in a balanced fund.

Bad news that you think might cause a market downturn: There is almost always a reason not to invest—economic uncertainty, geopolitical turmoil, natural disasters, or global pandemics, for example. And at times, macro events can result in deeply negative market returns, such as the 20.6% drop in response to the coronavirus pandemic in the first quarter of 2020, or the 19.4% market decline amid surging inflation and rising interest rates in 2022.

But the problem is that it’s impossible to predict how the market will react to any given event, or how long the decline will last. The drawdown in early 2020, for example, was surprisingly short-lived. Investors who sold off early in the year would have missed out on the market’s subsequent rebound, which more than offset the previous losses.

Fear of buying at the wrong time: This issue is closely related to the previous point. Investors often keep cash on the sidelines out of fear that they’ll invest close to a market peak, resulting in immediate losses. But statistically speaking, the market goes up more often than it goes down. As detailed in one of my previous articles, equity market returns are frequently negative over shorter periods: About 45% of trading days and 42% of weekly trading periods have historically ended up with negative returns. But that still means that positive returns are in the majority. Over longer periods, about two thirds of monthly and three fourths of annual returns have historically been positive for the equity market. Thus, keeping money on the sidelines is often a losing bet.

That said, reluctant investors who are paralyzed with fear about the prospect of deploying a lump sum at the wrong time might fare better with a dollar-cost-averaging approach, which involves investing consistent dollar amounts at regular intervals instead of all at once. This approach doesn’t usually optimize returns, but it’s better than not investing at all.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/SIEYCNPDTNDRTJFNF6DJZ32HOI.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/L5GEZ3AZXJFKNI7D64TOPM3RK4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/P627737FXRBCJMMKIHW7537BJU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)