Why Ultrashort Bond Funds Aren’t Cash Substitutes

These funds are generally cautious but can still suffer losses.

With interest rates now running well above their 2021 lows, investor interest is perking up in the short end of the yield curve. CDs, money market funds, and other cashlike assets are finally generating attractive yields for the first time in decades.

At the same time, however, investors have sold off ultrashort bond funds, which focus on investment-grade bonds with shorter-term durations (typically less than one year). The category—which raked in more than $260 billion in cumulative net inflows over the 10-year period ended in 2021—suffered about $9.2 billion in net outflows during 2022.

These outflows suggest a potential mismatch between investors’ expectations for safety and the performance they actually received. In this article, I’ll delve into why ultrashort bond funds aren’t a cash substitute.

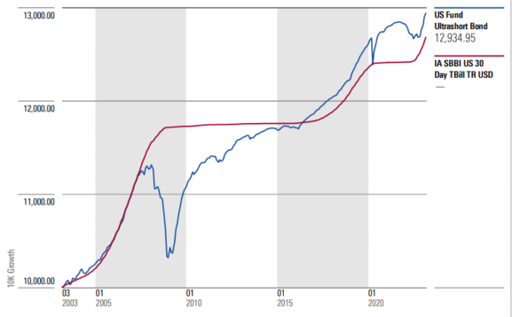

Ultrashort Bond Fund Performance Versus Cash

As the graph below illustrates, ultrashort bond funds haven’t matched the smooth ride offered by true cash assets (in this case, an index tracking the 30-day Treasury bill). That was particularly true in 2008, when the average ultrashort bond fund dropped 8.4%. As the housing market collapsed, securities that were previously thought of as safe, such as securities backed by subprime mortgages, floundered. The downdraft was exacerbated by selling pressure as many portfolio managers were forced to sell into market weakness to meet redemptions.

A few high-profile funds, such as Schwab YieldPlus, dropped even more. The fund had one of the highest yields in its category and was sold as a safe, higher-yielding alternative to money market funds. As the mortgage market unraveled in 2008, however, it lost more than 35%. Not only were holdings such as nonagency mortgage bonds much riskier than anticipated, but it had to sell off many of its holdings as shareholders fled en masse, further depressing prices on its holdings. Charles Schwab SCHW eventually agreed to pay $200 million to settle a federal class-action lawsuit for inadequate disclosure of the fund’s risks.

Fidelity Ultra-Short Bond Fund, which lost 7.8% in 2008, and SSgA Yield Plus, which lost 13.4% in 2007, suffered from similar issues, although the damage was less severe. All three funds have since been discontinued.

Although the disastrous results from the financial crisis haven’t been repeated, ultrashort bond funds again wavered during the pandemic-driven downturn in early 2020. While most investment-grade bond categories posted positive returns during the market’s flight to quality, the average ultrashort bond fund lost about 1.8% in the first quarter. Morningstar’s Brian Moriarty attributes this partly to their holdings in credit-sensitive securities such as bank loans, short-term corporates, asset-backed securities, and nonagency mortgage securities. Despite their low durations, these securities are still correlated with credit spreads, which was a negative as investors sought shelter in safer assets. Outflows from these funds during the flight to quality also forced portfolio managers to sell holdings, putting more pressure on asset prices.

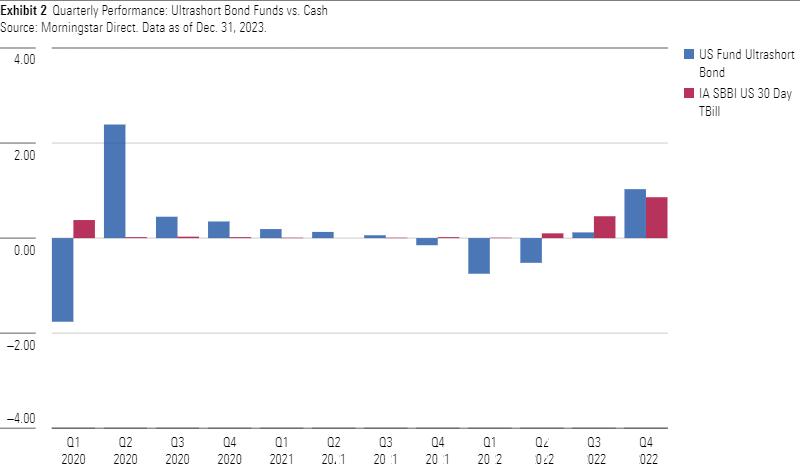

As resurgent inflation prompted the Federal Reserve to repeatedly hike interest rates during 2022, ultrashort bond funds were relatively resilient. As the chart below illustrates, they had small losses during the first two quarters but made back most of their losses by the end of the year. As rates rose, portfolio managers for ultrashort funds were able to reinvest proceeds from maturing bonds at higher yields, offsetting some of their previous losses.

What It Means for Your Portfolio

Because of their somewhat spotty history, ultrashort bond funds aren’t the best holding for short-term cash needs. As detailed in Morningstar’s new Role in Portfolio framework, they’re more appropriate for investors with a time horizon of at least one to two years. Even then, investors should proceed cautiously. If a fund offers a higher-than-average yield, it’s likely taking on more risk to do so—either by dipping into corporate bonds with middling credit quality or investing in more credit-sensitive sectors, such as structured credits. Investors will likely get a smoother ride in ultrashort bond funds that avoid esoteric strategies and maintain a sizable Treasury buffer, such as Baird Ultra Short Bond BUBSX, Pimco Enhanced Short Maturity Active ETF MINT, and Pimco Enhanced Short Maturity Active ESG ETF EMNT, which have Morningstar Analyst Ratings of Gold.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/SIEYCNPDTNDRTJFNF6DJZ32HOI.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/L5GEZ3AZXJFKNI7D64TOPM3RK4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/P627737FXRBCJMMKIHW7537BJU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)