What Happens When an Index Fund Changes Its Target Index?

Investors may not continue to receive what they first signed up for.

Index-tracking mutual funds and exchange-traded funds have a lot of endearing qualities. Many of them pair low fees with a clear set of rules, which has been a big win for investors. But those qualities don’t extend to every index fund. Many look very different from the broader stock and bond markets, and their backtests may paint a rosy picture that doesn’t always work out well.

Index-tracking funds also come with an implicit assumption: The rules that govern how a fund selects, weights, and trades stocks or bonds shouldn’t change. But that isn’t always the case. Some index funds change their stripes in big, small, bad, and good ways. Such modifications are akin to changing an actively managed mutual fund or ETF’s manager. Investors may not continue to receive what they first signed up for.

Morningstar’s new paper Transforming Index Funds: More Than Meets the Eye looks at index-tracking funds that have changed their target index and the impact that such changes have on investors.

Set It and Forget It?

Changing an index-tracking fund’s target index isn’t common, but it also isn’t rare.

Each year, Morningstar analysts typically place the Morningstar Medalist Ratings of a few analyst-rated index-tracking funds under review because the provider has decided to change their target indexes. These decisions represent investment process changes that potentially alter the funds’ risk/reward profiles.

Morningstar found that about one fourth of index-tracking funds in the sample set had switched target indexes at least once since their inception date (that is, 310 of roughly 1,200). And some of these funds swapped their benchmark more than once. In total, those 310 funds made 374 index changes.

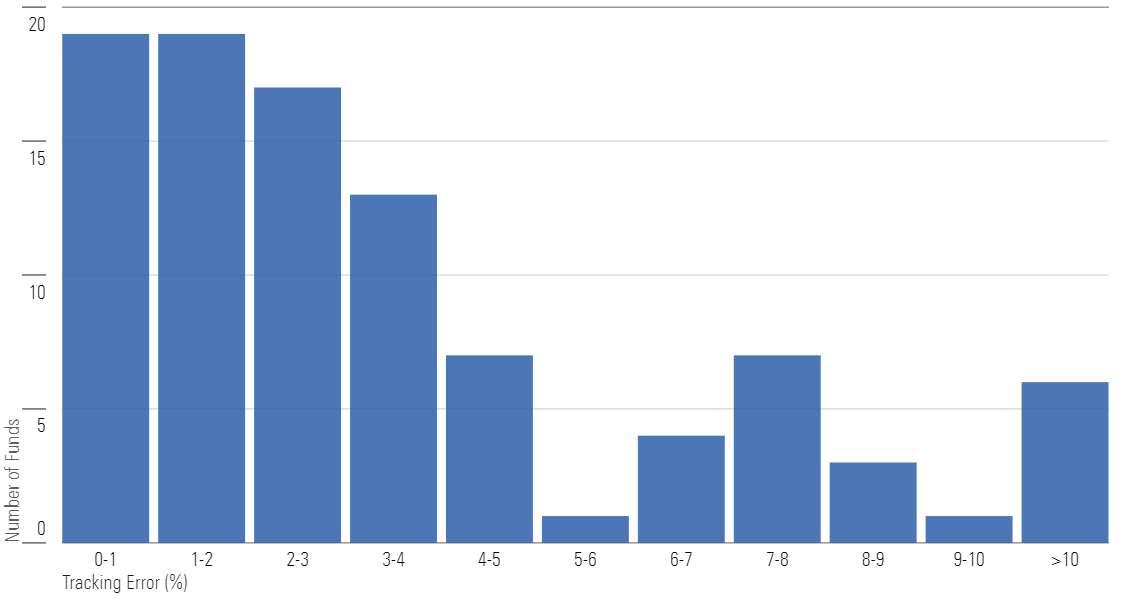

Calculating the tracking error between two indexes over a common period is one way to quantify the magnitude of any differences between them, and it helps sort minor changes from larger and more meaningful ones.

The chart below shows the distribution of tracking errors for 97 index changes with sufficient historical returns. Tracking errors were calculated between old and new indexes over the five years prior to the changes. Gross-of-fee index returns, not fund returns, were used in these calculations to remove the influence of fees and real-world transactions. Calculated this way, the measured tracking errors reflect the differences in index rules when the funds changed their targets.

Measuring the Impact With Tracking Error

Tracking errors below 3% usually corresponded with small differences between two indexes, and they represented the low tracking error cohort. In most instances, the index fund provider switched to a new benchmark that retains most of the rules of the old one, and nothing really changes from an investor’s perspective. These funds retain most, if not all, of their existing risk/reward profile.

Index fund providers like Vanguard and BlackRock typically make these modest changes for two reasons. One possibility is that they’re trying to lower costs. They pay licensing fees to index providers for the rights to track an index, and switching to a different index provider creates the opportunity to negotiate lower fees. Cutting those fees can benefit investors if the savings is passed along through lower expense ratios.

The other reason relates to the costs an index fund incurs when it trades stocks or bonds. A fund may swap out its index for one that’s similar but spreads trades out over several days or quarters. The goal is to reduce the hidden costs that stem from trading large amounts of a stock or bond on a single day. In these instances, the differences are usually so small that investors won’t notice the change.

The last change to Vanguard Total Stock Market Index’s VITSX target index exemplified these marginal adjustments. Vanguard’s flagship mutual fund changed to the CRSP US Total Market Index from the MSCI US Broad Market Index in June 2013. Both indexes represent the entire investable US stock market, and the tracking error between these two benchmarks supports that notion. It was just 0.26% over the five years before the switch—well below the 3% threshold. The main differences boil down to minor details that dictate how and when each index trades its underlying holdings. The MSCI index reconstitutes its holdings on two days per year, while the CRSP benchmark spreads its trading activity over four five-day windows.

More substantial and questionable differences arose in the high tracking error cohort, or those instances when tracking error exceeded the 3% threshold. Larger tracking errors indicated bigger differences between old and new indexes. Investors should pay attention to such changes. They likely won’t continue to receive the risk/reward trade-off that they initially signed up for, and they may have to reassess the investment merit of the new benchmark.

For example, Invesco S&P 500 GARP ETF SPGP replicated the Russell Top 200 Pure Growth Index prior to June 21, 2019. It has since tracked the S&P 500 Growth at a Reasonable Price Index. The tracking error between these two indexes was nearly 7% over the five years prior to the switch because they are very different strategies. The former focuses on stocks with the most expensive price multiples in the US market. The latter holds growth stocks, but those trading at lower multiples.

Less Money, More Problems

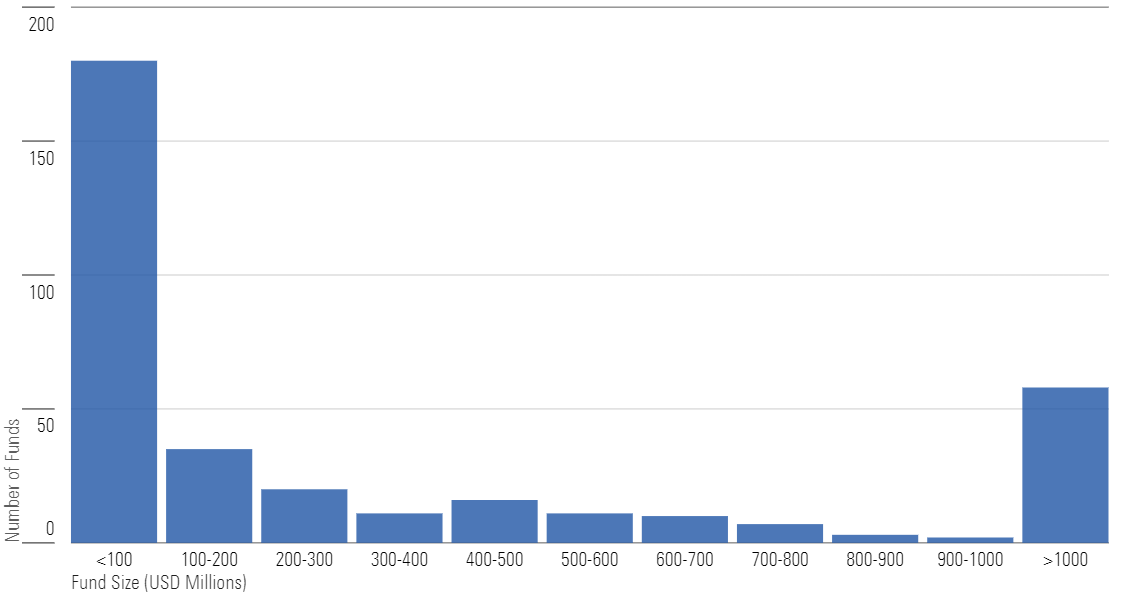

Funds that caused large changes when they swapped benchmarks shared a common characteristic: They were small.

Large funds that changed their target index tended to land in the low tracking error cohort. Often, they swapped out their old indexes for similar ones. Most of the funds in the low tracking error cohort (36 of 55) had more than $500 million in assets. Similarly, 32 of the 42 funds that had more than 3% tracking error between their old and new indexes had less than $500 million in assets.

Smaller funds also dominated the broader sample. As shown on the chart below, a little more than half the index changes for which fund size was available (180 out of 352) happened at funds with $100 million or less. Only 58 had $1 billion or more at the time of the switch.

Small Funds Were More Likely to Change Their Index

In other words, large index-tracking funds that changed their target indexes were more likely to incur minor changes, while smaller funds were more likely to experience dramatic shifts.

That makes sense. Fund providers have little incentive to meaningfully change the risk/reward profiles of large, viable, widely accepted index funds that are producing reliable revenue streams. It rarely happened in the sample set.

Smaller funds face an existential problem. They’re not very popular, and the costs of managing them can outweigh the little revenue they generate. Such funds might have to shut down if their situations don’t improve. Big changes to their target indexes may represent the marketing equivalent of a Hail Mary pass—a last-ditch attempt to increase their popularity and improve their odds of surviving and becoming profitable.

Changes to an index fund’s target index aren’t rare, and they tend to affect smaller funds with greater frequency and magnitude. Avoiding small funds is one way to steer clear of most problematic index changes. But that’s an insufficient approach because it ignores meaningful changes to large funds with the most investors.

Many of the index changes in the sample set were communicated to investors through SEC filings before they took effect. That said, index fund investors should monitor prospectus documents and amendments to those documents for such changes.

Index funds assigned to a Morningstar analyst will proactively identify such changes through an analyst note that’s appended to the top of Morningstar’s Managed Investment Reports. The Medalist Rating may be placed under review if the new index is sufficiently different from the current benchmark.

You can also use the “Focus Prospectus Benchmark Change History” data point in Morningstar Direct to view the history of an index fund’s target index. Funds that have tracked multiple indexes will show a chronological list of those indexes along with their effective date.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/78665e5a-2da4-4dff-bdfd-3d8248d5ae4d.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/NPR5K52H6ZFOBAXCTPCEOIQTM4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/09-24-2024/t_c34615412a994d3494385dd68d74e4aa_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/78665e5a-2da4-4dff-bdfd-3d8248d5ae4d.jpg)