When Will Public and Private Equity Markets Finally Converge?

New research highlights the challenges faced by the private equity market.

The investment world is abuzz with plans for mixing public and private assets in single vehicles that the masses can buy. Private assets, fund companies say, have been out of everyday investors’ grasp for too long, and they are eager to extend their hand.

Mutual funds, though, have been mixing public and private equities for years, though the SEC limits them to holding a maximum of 15% in such illiquid holdings in open-end funds. Much of the current excitement around private assets surrounds closed-end vehicles like interval funds. In those structures, fund companies can create portfolios made up entirely of private companies.

So, has private company equity ownership, in aggregate, helped or hurt investors in mutual funds? And what would that mean for the potential of private equity in interval funds or other closed-end vehicles? I examined those questions and more in my most recent research on mutual funds’ ownership of private company equities.

The results are not encouraging. Collectively, mutual funds would have been better off allocating their private stakes to public markets over the last 10 years. Further, the holdings are extremely illiquid because of structural features of the venture capital market.

As I will explain below, the findings suggest a challenging path forward for any mass-marketed funds, be they interval funds or exchange-traded closed-end funds, that plan to primarily invest directly in private company equities.

In Private Equity, Liquidity Is Everything

The biggest drawback of public vehicles owning private company equities is they are very hard to trade.

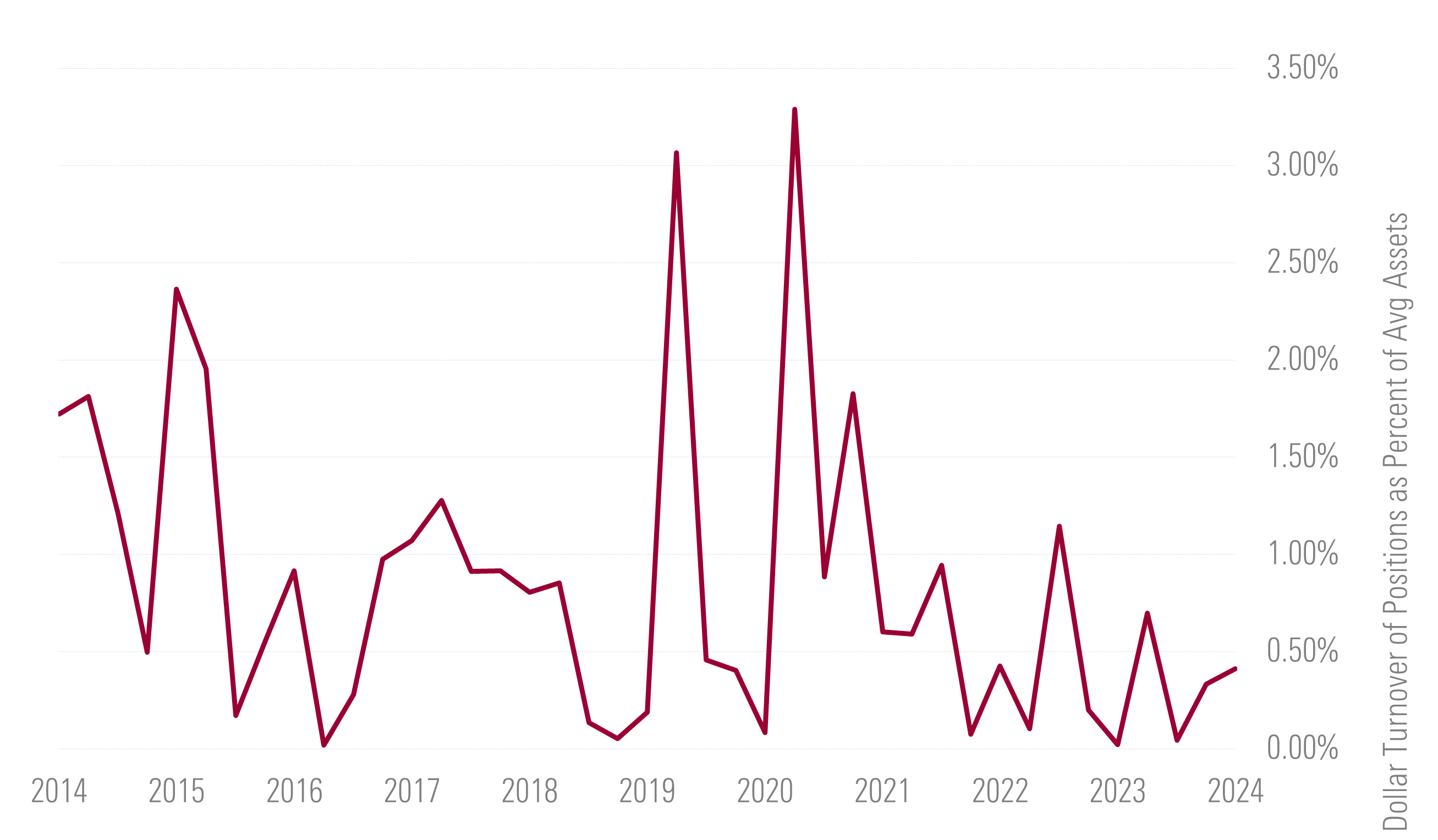

As shown below, on average, mutual funds buy or sell less than 1% of the private company shares they own per quarter. Funds’ adding to existing positions via new financing rounds accounts for most of that activity. True secondary market trades are much rarer. If you only look at sales of existing shares, a better proxy for secondary trades, the average quarterly turnover is roughly 0.3% of average assets. Simply put, once a mutual fund owns private company shares, it is usually stuck with them until an IPO.

Quarterly Dollar Volume Traded of Private Company Equites

No new vehicle or wrapper will solve this liquidity problem. A lack of private equity exchanges is not the issue; in fact, multiple competing platforms already exist. Rather, private companies’ illiquidity is a feature created by regulators and the startups themselves, not a bug.

Many companies stay private to avoid making the financial and other disclosures the SEC requires of public companies, which can be onerous. Private companies can only do that for so long, though. The SEC can require them to start public reporting once they have 2,000 shareholders, or 500 unaccredited investors, providing incentives to the startups to keep their shareholder list short.

Equity owners also tend to be more meddlesome than debt providers. Creditors don’t have as much say in how founders and executives run their businesses as equityholders do (that is, until bankruptcy, when bondholders get paid first and can dictate the terms of a reorganization). Private and public stockholders commonly seek to influence, and even change, company management and strategy, another reason private companies want to limit ownership.

To do this, private companies often reserve the right-of-first-refusal on any shareholder’s sale and can also flat out restrict secondary market sales altogether. This can complicate fund management.

Destiny Tech100 DXYZ, an exchange-traded closed-end fund that invests in private companies, for example, claims to have forward agreements to purchase shares of Stripe and Plaid. Both of those companies, however, have disputed those agreements and said they would not allow the transactions to happen. At the very least, the companies could enforce their right-of-first-refusal and step in and buy the shares, depriving the fund of ever holding them. For fundholders of Destiny Tech100, that means they paid for shares the fund never actually owned.

In most cases, a private company’s shares are only as liquid as the company allows them to be.

Does Private Equity’s Illiquidity Pay?

Given the lack of liquidity for private company equities, it would be fair to demand a higher return for investing in them. However, that does not appear to be the case.

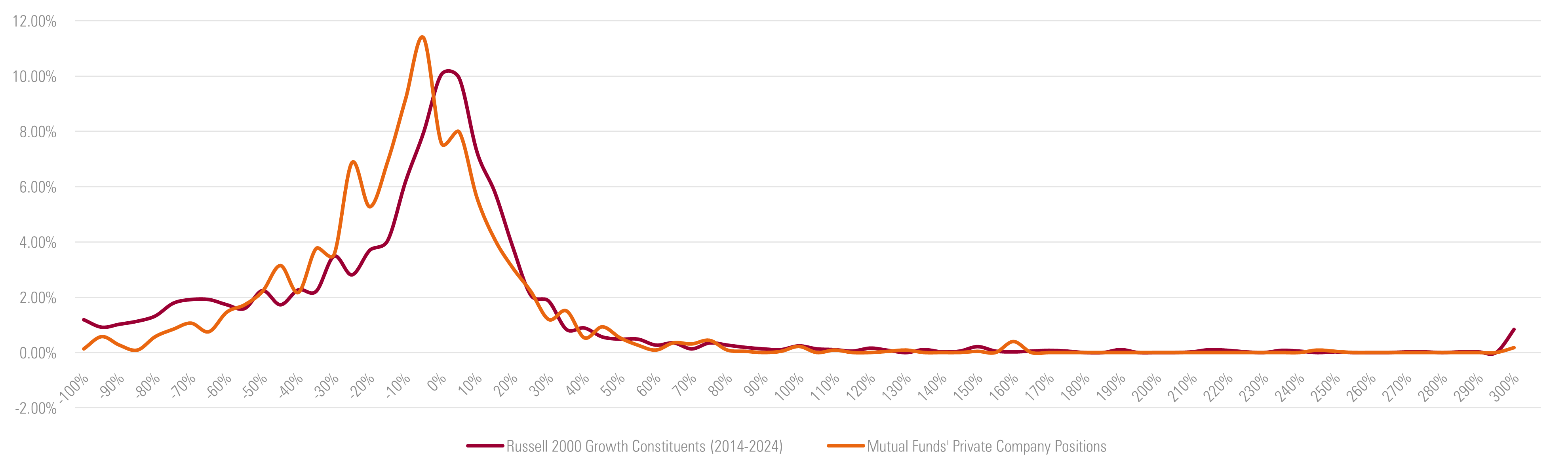

As shown below, mutual funds’ private company positions have lost value more frequently and seen fewer explosive winners than the constituents of the Russell 2000 Growth over the same time period. The distribution of mutual funds’ private company equity returns is skewed toward the left (that is, negatively), which does not make for a very attractive asset class, especially after considering the illiquidity.

Annualized Return Distributions 2014-24: Mutual Funds' Private Company Positions Vs. Russell 2000 Growth

This is not an indictment on venture capital overall. Rather, these disappointing results are a function of when mutual funds tend to get involved in private markets. Stock mutual funds typically want to invest in private companies with established business models that are generating revenue. Ideally, the companies are already on the road to an IPO, too, as mutual funds do not want capital tied up very long in illiquid assets.

Typically, mutual funds do not invest in startups’ riskier early-stage rounds. Mutual funds established about two thirds of their private company positions in Series D or later rounds. This means they already missed a lot of the upside of successful startups. The explosive venture capital gains everyone hears about accrue to a few, very early-stage investors. Once you get into funding rounds C and later, the potential for headline-grabbing, massive gains gets rare.

Have Mutual Funds Benefited From Owning Private Equity?

The IPO is not the end of the road for private equity investors. As pre-IPO owners, they are usually considered insiders who are subject to a customary six-month lockup period during which they can’t sell their shares. This restriction, it turns out, is very important.

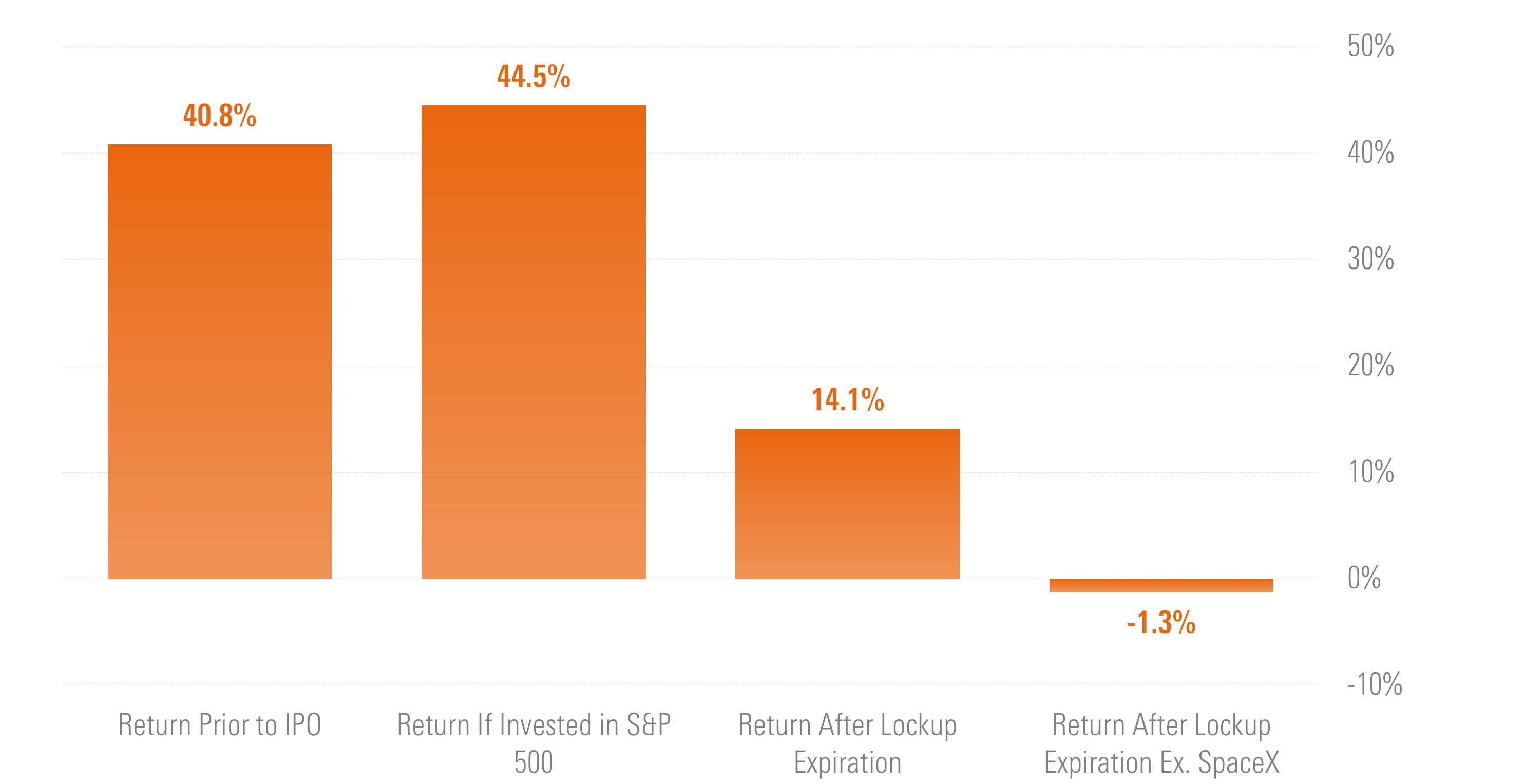

At first blush, the returns on mutual funds’ private stakes do not look terrible. They generated a roughly 41% return (that is, the absolute dollars made on dollars invested), slightly less than the 45% the funds could have earned by putting the same amounts in the S&P 500 over the same respective investment periods. However, several of the private stakes tanked following their IPOs, and the overall return after accounting for lockup periods was less than a third of the S&P 500′s.

Returns on Private Company Equity Positions in Mutual Funds

Further, a single company—SpaceX—buttresses the gain. Without Elon Musk’s spaceship company, mutual funds, in aggregate, have lost money on their private company equity positions. SpaceX’s gain is almost entirely unrealized, though. While the company’s shares, so far, have seemed destined to climb as high as the firm’s aspirations to fly to Mars, plenty of other high-flying startups have crashed back to Earth in a short time. Look no further than Rivian Automotive RIVN in 2021, which is down over 90% since its IPO.

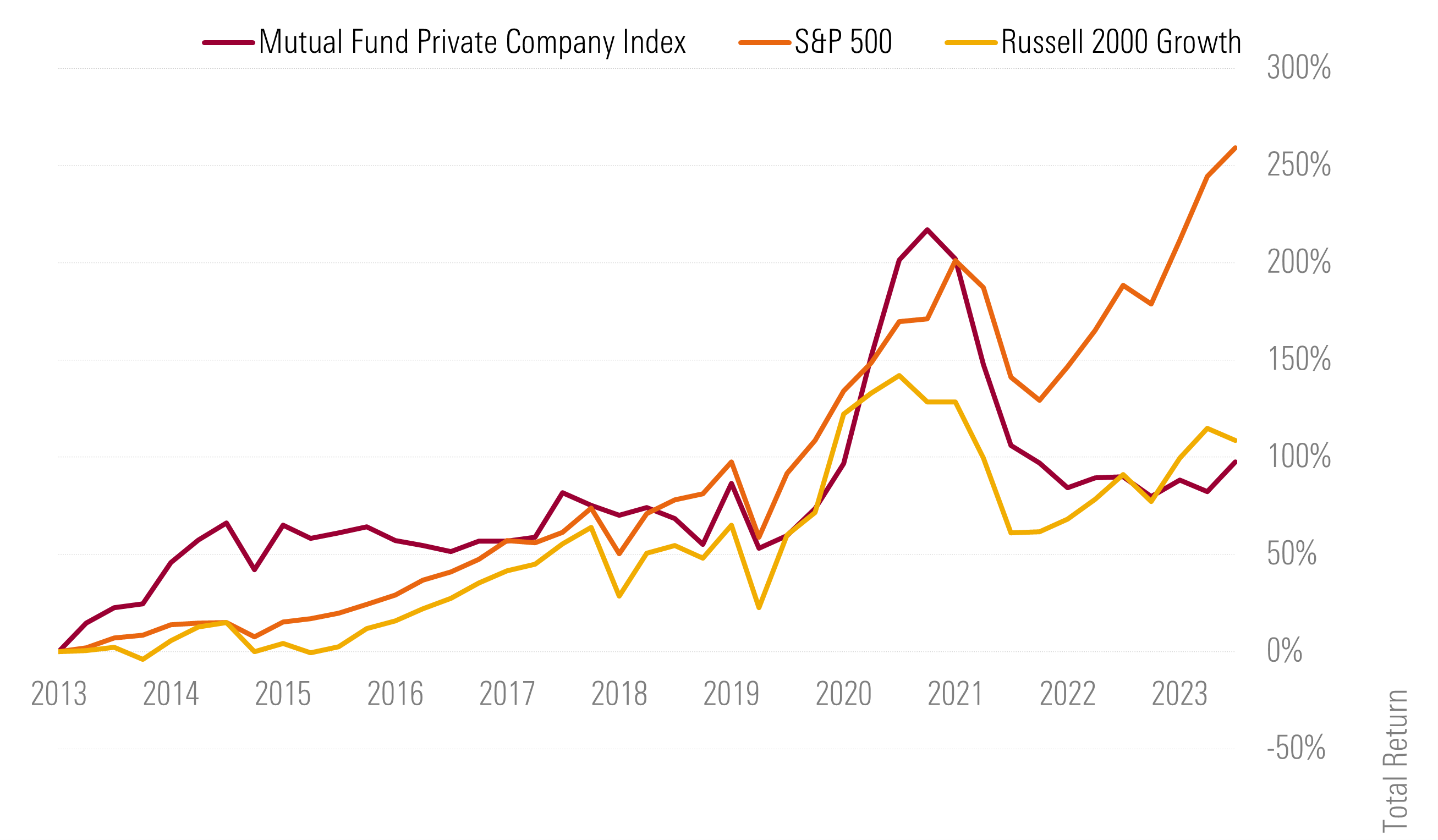

Even an investment in the aggregate portfolio of mutual funds’ private company equities would have disappointed. A portfolio that gathered all of mutual funds’ private company equity positions (on a dollar-weighted basis) and compounded the returns over time would have lagged both the S&P 500 and the Russell 2000 Growth from the end of 2013 through June 2024.

Returns Comparison

Should Private Equity Be Democratized?

“Should” and “could” are two very different questions, and the “should” answer is only relevant if the “could” answer is yes.

I would argue that, right now, funds that seek to directly own private company equities cannot be democratized at scale given the structural liquidity limitations.

Maintaining a portfolio of private company equities will be exceedingly difficult when liquidity is sparse and fundraising volume is low, even in a semiliquid structure like an interval fund that limits how frequently investors can withdraw their money. New inflows (or fresh capital raises in the case of closed-end funds) would either need to wait on the sidelines until new financing rounds or they will need to be deployed into less appealing companies.

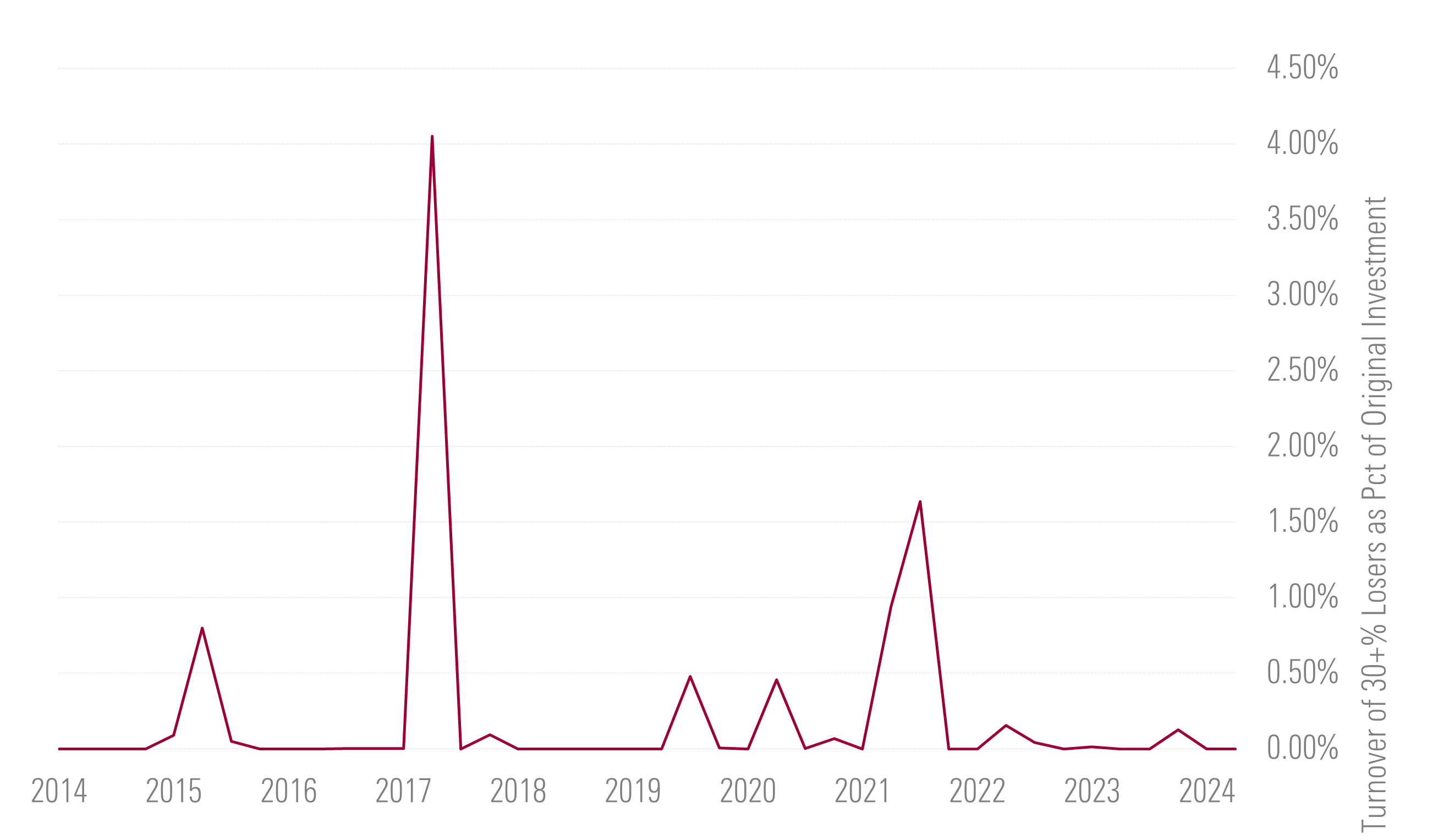

Outflows, which will likely occur during periods of poor performance, will create stark challenges. Interval funds only allow a small percentage of shares to be redeemed in a given time period, which helps prevent fire sales but also means not all investors will be able to exit if redemption requests exceed the quarterly limit. Funding the redemptions is a whole other issue. Mutual funds’ experience with the asset class demonstrates that selling losing positions is no easy feat. As shown below, mutual funds have barely been able to trade any private company after it declined 30% or more in value. Outside of a few anecdotal instances, mutual funds typically have to ride their losers into the ground.

Quarterly Turnover of Mutual Funds' Private Company Equity Positions That Were Down 30-Plus%

These problems won’t stop fund companies from trying to find ways to deliver private equity solutions to everyday investors. Given the liquidity issues, though, any attempt to invest directly in private company equities will be very difficult to pull off at scale and in an investor-friendly manner.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/b0c51583-b9a2-49eb-9a8f-5f25a8bda4a3.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/DOXM5RLEKJHX5B6OIEWSUMX6X4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/b0c51583-b9a2-49eb-9a8f-5f25a8bda4a3.jpg)