Revenue Exposure: A Different Way to Assess Fund Risk and Opportunity Globally

This approach isn’t revolutionary, but it has its value.

When China’s economy slows, or European regulators crack down on corporate tax loopholes, equity mutual fund shareholders might check their country or regional weightings—which are based on company domiciles—to see how these developments could affect their funds. But domicile—essentially a company’s nationality—isn’t the only relevant metric.

Some money managers think of their international exposure differently: where the companies they own reap their revenue. The approach has some merit. However, a closer look at the data shows that investors should not ditch the tried-and-true domicile-based method of determining geographic exposures.

Where in the World?

Asset managers and research firms such as Morningstar classify equity strategies by their geographical traits, as well as by style and market capitalization. Funds that focus on US-domiciled companies are considered US (or domestic) funds, and those with limited or no US holdings are foreign (or international or ex-US) funds.

That said, determining where a company is domiciled—essentially, its nationality—can be less than straightforward. Should a mining firm headquartered in London be considered a UK company even if all its mines are in South Africa? With that in mind, some investors and researchers argue that where a company does business can affect its fortunes as much as—or more than—the location of its headquarters or main stock listing.

This led to an alternative way to measure a fund’s geographic footprint: revenue exposure. Where does a company—or a portfolio of companies—get most of its revenues?

Since many big companies receive revenues from all over the world, looking at revenue exposure raises the intriguing possibility that the division between the US- and foreign-stock categories—which is based on domicile—would dissolve. If US-focused large-blend funds, say, own companies that receive similar levels of revenue from the US as those in the foreign large-blend category do, perhaps all of these funds should be in the same group. At the very least, these category divisions would require a rethink.

We looked at the data, and the results are clear: The traditional classifications still make sense. Revenue exposures between the corresponding US and foreign categories differ markedly. That said, revenue exposure does have its place. Used judiciously, it can provide a helpful, distinctive way to assess a fund’s opportunities—or vulnerabilities.

Theory Meets Reality

Morningstar Direct shows the combined percentage of revenue that the companies in an equity-fund portfolio derive from various regions. (Because companies can use different methods to report revenues by region—if they do it at all—these numbers are approximations.) If multinational giants routinely receive similar amounts of revenue from the US regardless of their domicile, then corresponding large-cap fund category averages would show similar US revenue exposure.

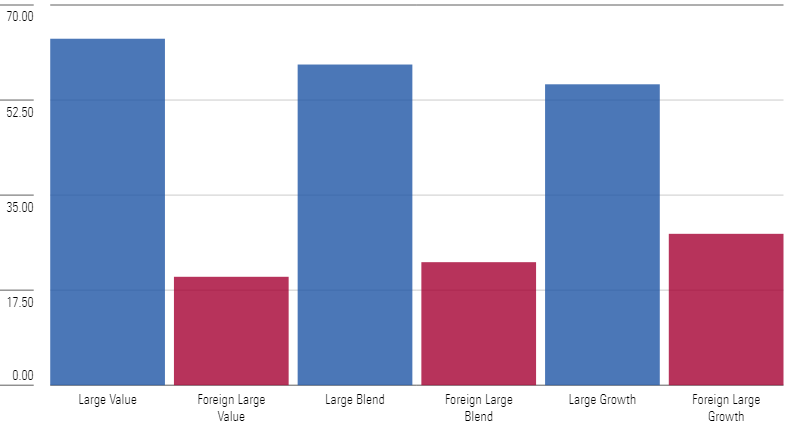

That’s not the case. When comparing the revenue-exposure figures for corresponding categories—large value versus foreign large value, large blend versus foreign large blend, and large growth versus foreign large growth—vast differences appear.

US Revenue Exposure by Morningstar Category

As shown above, the average US revenue exposure for the US-focused large-blend category is 59%, more than double the 23% figure for the foreign large-blend category. There’s an even greater disparity between the value categories: 63% US revenue exposure for large value, 20% for foreign large value.

The spread is less marked in the growth categories, but US large-growth funds still derive twice as much revenue in the US as their ex-US counterparts do.

Conversely, each foreign large-cap category has roughly double or triple the revenue exposure to the eurozone than the matching US-focused category.

Meanwhile, one would expect small and midsize companies to focus mainly on their local regions, and the revenue data supports that idea. The US exposure for the small-blend and mid-cap blend categories are 83% and 74%, respectively, while the US exposure for the foreign small/mid-blend category is a mere 14%.

Beyond the Averages: Fund vs. Fund

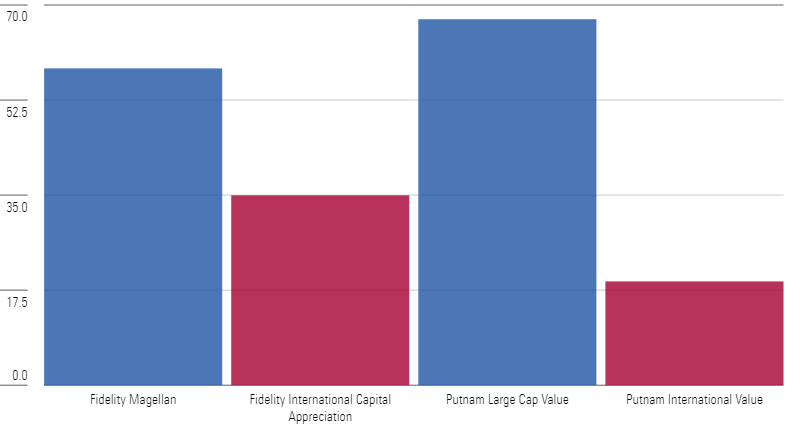

Category averages thus validate the practice of dividing funds into categories the traditional way. But perhaps similar revenue exposures appear in individual pairs of US and foreign funds? For example, Sammy Simnegar runs both Fidelity Magellan FMAGX—which has more than 95% of its assets in US-domiciled companies—and Fidelity International Capital Appreciation FIVFX, which has only 9% in them. He runs the funds in a similar style, and both portfolios have very high average market caps.

Their revenue exposures, though, aren’t close. Fidelity Magellan receives 58% revenue from the US, while Fidelity International Capital Appreciation’s figure is 35%.

The disparity is even greater between a pair of Putnam offerings. Darren Jaroch runs Putnam Large Cap Value PEYAX and Putnam International Value PNGAX with a similar quantitative approach. The US-focused Putnam Large Cap Value has US revenue exposure of 67%; the figure for his international charge is just 20%.

US Revenue Exposure of US and ex-US Funds Run by Same Manager

Two More Factors to Consider

There’s another reason not to discard traditional domicile classifications: currency movements. Most funds available to US investors do not hedge their currency exposure. When they buy a Japanese stock, they generally do so on the Tokyo market and pay for it with yen. When calculating their net asset values, US-based funds must translate that stock’s value into US dollars. As a result, when the yen falls sharply, the currency translation can dent or even wipe out the gains from successful Japan stock picks. Had the fund owned similar companies based in the US with the same stock-price gains, those gains would have remained intact.

Geopolitical events also highlight the importance of domicile. In late February 2022, US-based mutual funds suddenly had to value the stocks of Russian companies in their portfolios at zero. It didn’t matter where the company’s revenue came from; in fact, Russian energy firms derived plenty of revenue outside Russia. Their Russian domicile is what mattered. True, that’s an extreme example—European wars don’t break out every day—but less dramatic cases exist. Many fund managers have become wary of owning companies based in China because in recent years that country’s government has impaired the prospects of several industries with strict regulations that few had seen coming. The managers’ caution is based on domicile, not revenue exposure.

What’s the Use?

While the above data illustrates that traditional classifications and categories are still important, revenue exposure does have its place.

For example, shareholders of an international fund that owns very few US stocks may think the fund will feel scant effect from the ups and downs of the US economy. But take another look at Fidelity International Capital Appreciation. It receives much less revenue from the US than Fidelity Magellan. But at 35%, its US revenue exposure is much higher than its 9% domicile weighting. Armed with that knowledge, investors looking to diversify US-heavy portfolios may prefer a foreign fund that’s more fully foreign.

Revenue exposure need not revolutionize the way investors look at their funds. But it can provide a useful, different angle for investors to assess risk and opportunity.

Note: Graphics assistance provided by manager research analyst Tony Thorn.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/657019fe-d1b1-4e25-9043-f21e67d47593.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/AGAGH4NDF5FCRKXQANXPYS6TBQ.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/RSZNI74R6FG7FDSWBUF6EWKDE4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/NPR5K52H6ZFOBAXCTPCEOIQTM4.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/657019fe-d1b1-4e25-9043-f21e67d47593.jpg)