When Funds Avoid China, Where Do They Go?

Emerging-markets managers who shun the country disagree on the best alternatives.

Not long ago, China held tremendous allure for investors. While the excitement didn’t match today’s stock market frenzy over weight-loss drugs and artificial intelligence, trendy tech names such as Alibaba BABA and Tencent appeared daily in the financial headlines. Emerging-markets managers scrambled to ensure they had sufficient exposure to China’s market. With the number of listings increasing and stock prices rising, China dominated the MSCI Emerging Markets Index; at the high point, in October 2020, China had a remarkable 42.8% share of the benchmark.

The giddy feeling didn’t last. China’s market fell out of favor. Several factors share the blame: China’s real estate crisis and slowing economy; government interventions that derailed the prospects of fields like online education and video gaming; and the uncertainties resulting from the rising tensions between China and the US.

Through selling and market depreciation, the China stakes of emerging-markets portfolios shrank. Although China remains the MSCI Emerging Markets Index’s largest component, its weighting has dropped to the mid-20% range. The average fund in the diversified emerging-markets Morningstar Category is below that at 22%. Many have much lower weightings. Moreover, in a step that would have been unthinkable a few years earlier, asset managers launched a spate of emerging-markets funds that exclude China altogether.

Whether managers totally avoid China or merely hold a deep underweight, the question arises: Where do they invest instead?

First, the Obvious Choices

Plenty of other markets beckon. But to provide a viable alternative to China, a market must offer a respectable number of worthwhile stocks. For managers of emerging-markets funds with large asset bases, key concerns are the ability to buy a stock without pushing up its price before the purchase is complete and the likelihood of finding buyers when the time comes to sell. Only a few emerging markets offer the depth and liquidity to meet that standard. Thus, it’s not surprising that the favorite destinations for the ex-China funds, in particular, are India and Taiwan. At nearly 18% each, those two are essentially tied for the second-largest weighting in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index behind China.

William Blair Emerging Markets ex China Growth WXCIX makes major commitments to those two markets. In fact, it takes that theme to an extreme. According to Morningstar’s classifications, its May 31, 2024, portfolio had 32% of assets in India and 24% in Taiwan (with 14% of the latter stake consisting of a single stock, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing TSM).

However, many managers have made other choices. What stands out is the variety of responses taken by fund managers who have relatively little exposure to China or none at all.

India and Brazil

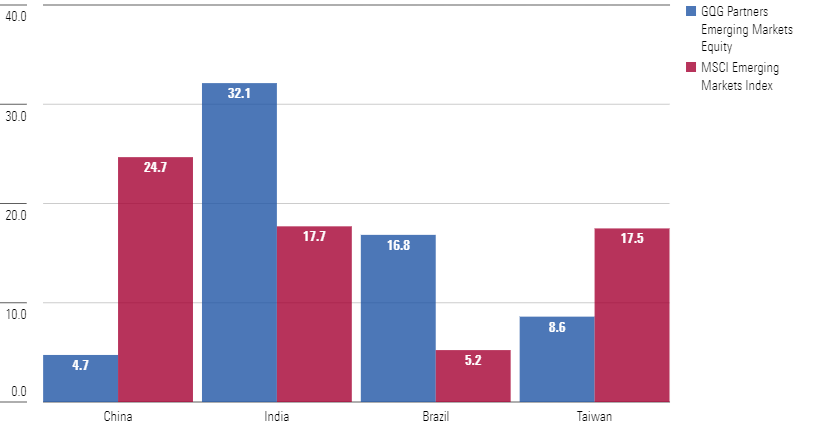

For example, while GQG Partners Emerging Markets Equity GQGIX—which has only 5% of assets in China—also leans heavily on India, Taiwan gets short shrift. In March 2024, that fund had 32% of assets in India (according to Morningstar’s classifications), nearly double the benchmark level and category average. At 9%, Taiwan’s weighting in the portfolio was only about half the levels in the index and category average.

The GQG fund’s India tilt isn’t merely a reaction to lead manager Rajiv Jain’s current aversion to China, or to the fact that in early 2022 he had a double-digit stake in Russia that also needed a new home. Jain has often favored India. He finds many well-run, growing companies in that country and says its favorable demographics provide a tailwind. Currently, he thinks many of these firms stand to benefit from the Indian government’s major infrastructure push.

Jain’s second favorite market is Brazil. A GQG research piece states that the country’s structural reforms over the past decade “have positioned Brazil for continued outperformance.” Brazil received 17% of assets in the GQG fund’s March portfolio, more than 3 times the index’s weighting and double the stake of the average emerging-markets fund.

GQG Partners Emerging Markets Equity's Country Weights vs. MSCI Emerging Markets Index

The managers of Morgan Stanley Institutional Emerging Markets Leaders MELAX raise Jain’s optimism on India and Brazil to the next level. That fund’s March portfolio had 44% of assets in India and 22% in Brazil, according to Morningstar’s data. (Morgan Stanley lists Brazil at 15%, likely owing to a different domicile classification for MercadoLibre MELI—either way, it’s a huge overweighting.) This fund has a very small stake in China; its first-quarter commentary explains that, in the managers’ view, the Chinese government’s failure to address structural problems will continue to restrain growth.

A similar level of enthusiasm for India and Brazil can be found in Calvert Emerging Markets Focused Growth CEMAX. That fund has 37% of assets in India and 24% in Brazil.

Other Paths to Follow

However, not all emerging-markets funds with little or no exposure to China devote more than half their assets to India and Brazil. Others take quite different paths. Virtus SGA Emerging Markets Equity PICEX, which acquired new managers in late 2023 when SGA replaced Vontobel as subadvisor, had less than 10% in China in SGA’s first portfolio. And while India and Brazil do take the top two spots here, only about 30% of assets combined go to those countries.

Instead, this fund’s managers heavily overweight Mexico. That Latin American market receives nearly 10% of assets, more than 3 times the level in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. (The GQG fund has just 2% in Mexico.) Next in line is another location that emerging-markets managers typically don’t devote this much attention to: Hong Kong. (MSCI considers it a developed market, not emerging.) That’s an interesting choice; depending on the stocks in question, Hong Kong can provide exposure to China without direct ownership of mainland stocks.

Spreading the Wealth

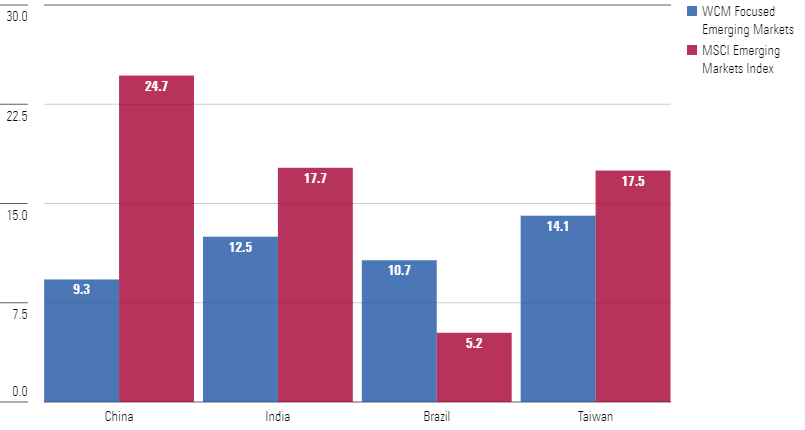

The above review might imply that despite their differences of opinion on markets such as Taiwan, Brazil, and Mexico, all of the little-or-no-China strategies rely heavily on India to fill the gap. Not so. Take WCM Focused Emerging Markets WFEMX. With only 9% of assets in China, this fund has every opportunity to load up on India as so many peers do. Instead, these managers recently chose to underweight India by 5 percentage points versus the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. They spread their bets widely, with no destination getting too much attention. Ten different markets, starting with Taiwan and ending with Indonesia, land in a range between 14% and 4% of assets. This is deliberate. The managers have told Morningstar that having downplayed China, they would rather not make a huge commitment to any other market.

WCM Focused Emerging Markets' Country Weights vs. MSCI Emerging Markets Index

Then there’s Seafarer Overseas Growth and Income SIGIX, which is not labeled as an emerging-markets fund but has the portfolio of one. This fund—with a meager mid-single-digit stake in China—does feature a heavily overweight market. But it’s neither India, Taiwan, nor Brazil. Instead, the managers place 21% of assets in South Korea. (The index is in the low teens.) Among other things, co-lead manager Andrew Foster likes the fact that many Korean companies have substantial amounts of cash they could distribute to shareholders, especially in view of recent government incentives to enhance shareholder value. After Korea, though, he and his colleagues follow with six markets allotted between 5% and 10% of assets, none significantly overweight versus the index. India receives just 8.5% of assets.

Buy American?

A small number of managers with little or no China exposure search for opportunities outside emerging markets. The WCM fund mentioned above has a mid-single-digit stake in companies based in the United States. Amana Developing World AMIDX goes further, with 21% of assets in the US, including number-one holding Nvidia NVDA at 8%. It has another 10% in the United Kingdom. GQG Partners Emerging Markets Equity also has 8% in Nvidia, making up the bulk of its stake in the US.

Emerging-markets managers who own companies based in the US or other developed markets typically defend those choices by arguing that the companies receive so much revenue from emerging markets that their formal domicile is of questionable relevance. (Separately, some companies that most would agree are essentially emerging-markets firms may show up as UK- or US-based merely owing to a headquarters or stock listing in London or New York.)

American Funds New World NEWFX took this idea further when it was founded in 1999. It explicitly divides its portfolio—at times roughly evenly—between companies domiciled in emerging markets and those that aren’t. Few others have taken that tack, though Artisan Developing World ARTYX has an even larger US stake than New World in its most recent portfolio, at 37% versus New World’s 21%.

Return of the Dragon?

Just because these funds—and others with little or no exposure to China—manage to fill their portfolios doesn’t mean it’s simple to do so. Or that it’s ideal for emerging-markets funds to have minimal stakes in the largest market in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. It wouldn’t be surprising to see the tide turn before too long. One impetus could be the recent election results in India and Mexico, both of which were received poorly by global investors. The strong performance of China’s stock market in early 2024 could also provide a spark.

It’s also worth noting that managers who own few China stocks or none still have some exposure to that country’s issues through the companies they own that sell products or services in China or which can be affected by China-linked supply-chain problems or other concerns.

One successful manager who believes in China’s investment potential is Sam Polyak, who runs Fidelity Advisor Focused Emerging Markets FAMKX. This fund’s latest portfolio had 33% of assets in China and just 10% in India. Polyak has told Morningstar he thinks his China holdings are strong businesses and that after the decline of sentiment toward that market, many stocks are at attractive valuations.

The funds that continue to shun or downplay China may eventually find it challenging to continue locating enough truly appealing opportunities elsewhere. Russia’s off the table, and while it didn’t constitute a large portion of the index, before 2022, it was very common to see several Russian stocks—Lukoil, Gazprom, Sberbank, and Yandex, in particular—near the top of emerging-markets portfolios.

South Africa’s recent election results could increase that country’s appeal. Some emerging-markets managers already had meaningful stakes there. In its most recent portfolio, Lazard Emerging Markets LZEMX had 6% of assets in that market. But at less than 3% of the index, South Africa doesn’t offer a big enough stock market to meet the needs of a manager looking to fill the void created by a small China stake. Meanwhile, India can’t provide all the answers; several emerging-markets managers we’ve spoken with in recent months say that after a long, powerful rally, India’s market has become extremely expensive.

With alternatives thus limited, perhaps a return to China is inevitable. If not, will more emerging-markets managers look to the United States and other developed markets to fill their portfolios? If they do, at what point would they be considered globally focused funds with notable emerging-markets exposure instead of dedicated emerging-markets portfolios? That complex question must await another day.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/657019fe-d1b1-4e25-9043-f21e67d47593.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/AGAGH4NDF5FCRKXQANXPYS6TBQ.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/5IGQZ5PHNZAIROE5WHJLOTZ35Q.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/VPCBITMQP5FKLIZ32POIXOV3MQ.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/657019fe-d1b1-4e25-9043-f21e67d47593.jpg)